A MATTER of days after the Christchurch Mosque Massacre, in which 50 people were murdered and as many seriously injured, both sides of New Zealand’s parliament bundled through a ban on semi-automatic weapons, including the firearm used in the massacre, the ArmaLite AR-15. The move poses questions over formerly soft gun laws in NZ, as well as highlighting challenges ahead for Australian law makers.

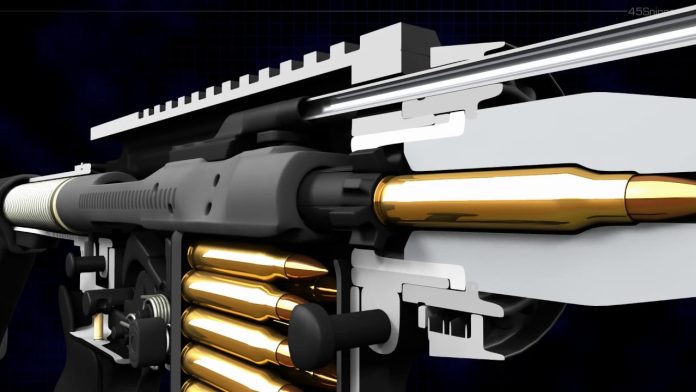

The AR-15 is the civilian version of Colt’s ubiquitous ArmaLite M16. Having fired this latter weapon on an Australian Army firing range I can attest to its qualities. The M16 is light, has minimal recoil, is compact and accurate. It’s also effective at close ranges, unlike military predecessors, such as the longer and heavier SLR. And because of the mechanical relationship with the M16, the AR-15 firing mechanism can be readily customised to a fully automatic specification without loss of its inherent qualities. But the strengths of this weapon on a military firing range make it a nightmare for law enforcement professionals on the street.

One question is how a near mil-spec weapon used in so many horrendous slayings was not already heavily regulated in NZ. This is the weapon that was used to kill and wound 62 in and around a Port Arthur café, 14 at 49th Street Elementary School, 80 at an Aurora movie theatre, 53 at a Sandy Hook primary school, 35 in San Bernadino, 99 at Pulse nightclub in Orlando. The AR-15 was used to kill 58 and wound 422 at a Las Vegas music festival, 26 at a church in Sutherland Springs and 34 at Stoneman Douglas High School just last year. Now, in Christchurch, the then unregulated AR-15, was used to murder 51 and seriously injure 50.

Closer to home, a key question is whether Australia’s existing gun laws need re-visting. Australia introduced restrictive licensing and policing of firearm categories after the Port Arthur massacre, in which 35 were murdered and 27 injured by a shooter armed with an AR-15 fitted with a custom 30-round magazine. But these restrictions have not stemmed the flow of illegal semi-automatic weapons, nor have they removed the relentless pressure to relax laws in Category C, which covers rim-fire semi-automatic rifles with 10-round magazines, as well as pump-action shotguns.

While most dedicated hunters prefer bolt-action long guns for larger game – these have greater range and larger calibre rounds with more stopping power – some primary producers want semi-automatics, particularly to address stock euthanasia during drought or after fires. These needs are legitimate – there are horror stories of sobbing farmers spending days shooting hundreds of dying animals with single-shot bolt-action rifles. There’s also pressure from a minority of sport shooters, who want high powered semi-automatic weapons for target shooting on firing ranges, as well as for hunting small game. The pressure isn’t just from special interest sports groups, whose requests for use of such weapons in highly controlled environments might be safely managed – it’s political. The recent NSW elections are likely to increase this pressure considerably.

Something else to consider is that there are now more weapons in Australia than there were prior to the gun buy-back after Port Arthur, at which time polls showed 90 per cent of voters supported more restrictive gun control. Recent polls suggest support for strengthening existing laws remains high and recent events suggest the public’s unease is evidence-based. Modifiable semi-automatic weapons in the hands of individuals intent on wreaking maximum harm pose a serious threat to the general public, especially in crowded places. Law enforcement and security professionals should make their voices heard in this debate and law makers in Australia must soberly consider their responsibilities.

#securityelectronicsandnetworks.com